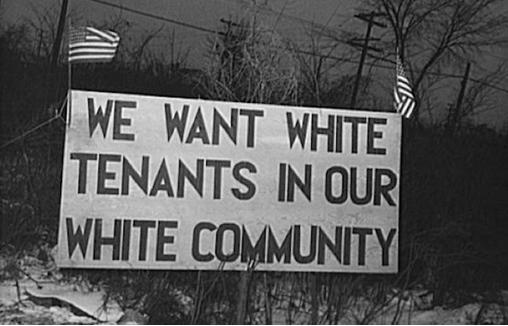

After San Francisco was devastated by the 1906 earthquake, an infamous tide of racial restrictions in deed covenants were instituted to limit the unprecedented growth of Japanese residents in formerly all-white communities. [ref] Horiuchi, Lynne. “Object Lessons in Home Building: Racialized Real Estate Marketing in San Francisco.” Landscape Journal, 26:1 (Spring 2007): 61-82. [/ref] In response to the post-war mass migration of African Americans to Baltimore from rural regions, the city sought to protect white middle class real estate from “crime and contagion” by implementing segregation ordinances through the legislative process. [ref]Ibid[/ref]And in an investigative piece for Chicago Magazine, Whet Moser cites a 1995 study of Chicago housing discrimination from 1967 to 1988 conducted by Brandeis sociologist Thomas Shapiro and co-author Melvin Oliver, explaining that, “Between reduced housing appreciation, higher mortgage rates, and lower approval rates, Oliver and Shapiro estimate that the combined cost to black homeowners of that generation was $82 billion.”[ref] Moser, Whet. “Housing Discrimination in America Was Perfected in Chicago.” Chicago Magazine, May 5, 2014. Accessed June 4, 2015.[/ref] What Americans have been tolerating, and even endorsing for the past century, then, is not only a blatant pattern of housing segregation, but also the institutionalized theft of the wealth of communities of color for the sake of some perverse sense of tribal loyalty. Fortunately, as Margery Austin Turner of the Urban Wire submits, recent surveys indicate huge declines in the number of whites opposed to living in communities with black neighbors, but the fact remains—“minority home seekers are still told about and shown fewer homes and apartments than equally qualified whites.” [ref] Turner, Margery Austin. “Housing discrimination today and the persistence of residential segregation.” Urban Wire: Neighborhoods, Cities, and Metros, June 12, 2013. Accessed June 4, 2015.[/ref]

Policies and practices geared toward neighborhood homogeneity are so problematic because housing determines one’s access to efficient transportation, green spaces, decent schools, adequate jobs and quality services.[ref] Moser.[/ref] So when members of specific communities, ethnicities and races are ousted from largely white, more affluent neighborhoods, their chances of achieving greater success later in life are severely curtailed. Add to the picture the subtlety with which most housing segregation practices today are carried out, and one begins to get a glimpse of just how insidious they truly are. The vendetta here, then, is the conflict between the equitable provision of public goods to members of disparate communities, and affording to individuals the right to live where they please.

As surveys illustrate, most people today believe that Chicago’s neighborhood make-up is “the work of organic sorting, not segregationist social engineering.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref] This is a convenient narrative, and one that serves to ease the conscience of countless voters, members of certain homeowners associations, and far too many landlords. The hard fact remains, though, that in Chicago particularly—and in several other cities across the U.S.—African Americans are living in areas where the riots of the late 1960s took place, which are “almost entirely African American today.”[ref] Samuels, Alana. “Is Ending Segregation the Key to Ending Poverty?” The Atlantic, February 5, 2015. Accessed June 3, 2015.[/ref] As mentioned above, most of these areas tend to be characterized by inadequate schools, poor transportation options, narrow job markets, concentrated poverty, and high crime rates.

Policy prescriptions aiming to rectify discriminatory practices of the past vary in scope, but a number of policymakers across the country have resolved to take the route of housing vouchers—using public funds to subsidize, in whole or in part, struggling inner-city families’ transitions to suburban, predominantly white neighborhoods. In fact, this approach has been shown in several instances to be extremely life-altering for these families, as was apparent in the Gautreaux program, implemented after a 1966 civil rights case resulted in a consent decree issued to the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) ordering the entity to provide vouchers to black families to move to white suburbs.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] At the federal level, the Department of Housing and Urban Development in 1994 implemented its Moving to Opportunity program through which distressed families from inner city projects in cities like Chicago, LA and Baltimore were given vouchers to move anywhere of their choice, and the results were not as outstanding as those of Gautreaux.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Notably, most experts who have comparatively studied the two programs agree that Moving to Opportunity failed because the families were not encouraged to move to majority white areas, attesting to the role that race still plays in determining one’s life outcome.[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

Essentially, voucher programs are market-based solutions to rectify discriminatory and predatory housing practices of the past in an era of unprecedented low levels of urban investment by federal and state agencies. The programs effectively redirect funding toward relocating hundreds of carefully selected inner city families to white suburbs, and would otherwise be used to better the quality of life for families left behind. Thus, underlying, systemic causes of inequitable housing and service access remain unscathed. Combatting the symptoms of chronic ailments like discriminant and segregated housing practices is not enough—federal urban policy is needed to invest in underserved communities to the extent of Roosevelt’s New Deal and Johnson’s Great Society. These funds should be directed toward repairing our crumbling infrastructure in order to provide steady, well-paying jobs to low- and semi-skilled workers; toward providing good access to public transportation and decent schools; toward the economic development of urban cores to provide low-income communities with walkable commercial corridors in which they can purchase essential goods at reasonable prices. Affordable housing, also, must be spread evenly throughout neighborhoods and municipalities to allow for low-income and minority residents to move to white, suburban communities that consistently have the best schools and the lowest crime rates. Exposing children to cultural diversity is widely recognized as a key component in the development of their personal beliefs, attitudes and behaviors,[ref] Kansas State University Newsroom. “Early Exposure to Diversity Good for Children.” Newswise, December 5, 2005. Accessed June 3, 2015.[/ref] so it is to the benefit for families of all income levels, races, and ethnicities to support policies that render our communities, urban and suburban alike, more culturally and socio-economically diverse.

Take Action:

Again, housing discrimination, though painfully common, is hard to detect, and even harder to prove. Fortunately, overt acts of discrimination like redlining have been federally prohibited since the Fair Housing Act of 1968, and more obscure strategies are being combatted more frequently in court. If you believe that you or someone you know have been victimized by discriminatory practices, you can file your Housing Discrimination Complaint online at U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.